Photo: A tailor’s shop, & echoes of a certain Georgia folk artist, Ixtapalapa, Mexico, D.F., May 2013. [RF]

Photo: A tailor’s shop, & echoes of a certain Georgia folk artist, Ixtapalapa, Mexico, D.F., May 2013. [RF]

The mighty Orquesta Basura played a free set this weekend at the Antiguo Colegio de San Ildefonso, in Mexico City’s historic center. The capital generates 12,000 metric tons of trash daily, and an estimated quarter-million people make a living of one kind of another off of trash, including pickers, recyclers, haulers–and these four musicians.

They make their instruments out of junk (including the helmet mounted “trompe-cabezas” trumpet, above), and their repertoire is a sweet-smelling salvage job that picks over some of the best semi-forgotten popular dance styles from around the world: tango, gypsy jazz, klezmer, polka, &c. Fitting for a city whose most beloved taco comes from Lebanon.

Here’s the Orquesta playing “Besame Mucho” at a 2011 festival:

Photos: [RF]

Originally posted at www.latimes.com:

TONATICO, Mexico — Armando Guadarrama was navigating his taxi through the narrow streets of this central Mexico pueblo on a recent Saturday morning, some 2,000 miles from the Beltway.

But like many here, Guadarrama was up-to-the-minute with the immigration reform push that is the talk of Washington. When he spoke of its odds, the 40-year-old could sound like a hard-bitten D.C. veteran, grumbling over a scotch at the Old Ebbitt Grill.

He sniffed incredulously at President Obama‘s statement, a day earlier, that he was “absolutely convinced” that reforms would pass this year. Did Obama really think that enough conservative Republicans would fall in line?

“They’re always making promises,” Guadarrama said. “They promised immigration reform” — over and over, he noted — “when I was living up there.”

But if a bill did pass, he emphasized, his family would benefit immeasurably: His older brother, who works in Illinois without a green card, would probably return to Mexico for the first time in 17 years.

The brother was too scared to come back for his father’s funeral in April, because security is so tight at the border. He was afraid he would be caught and deported — forced to give up his American life and paycheck.

Guadarrama’s thoughts summarize the two prevailing sentiments that Washington’s revived immigration reform effort arouses in Tonatico, a small, handsome old pueblo two hours south of the Mexican capital that has sent thousands of its sons and daughters to the U.S. to seek their fortune.

Many here are skeptical of reform’s chances in a polarized Washington. But they also hope they are wrong, because a law with a so-called path to citizenship would allow those who sneaked into the U.S. or overstayed their visas to finally return, without fear, to Mexico and see their loved ones.

“If the law passes, it will change a lot,” said Rafael Aviles, 43, a photographer who lived in Illinois for two decades before a number of run-ins with the law led to his deportation. “People will come back and spend a lot of time with their families. They will relive the life they left. A lot of people haven’t been back in 20 years.”

The details of the Senate’s bill were made public last month by the bipartisan group of eight senators whose proposal would allow those in the country illegally to attain “registered provisional immigrant” status if they pay taxes, fines and fees, pass a criminal check and prove they have lived in the U.S. continuously since Dec. 31, 2011. A small group of House lawmakers reported this week they had reached consensus on a parallel bill. Both bills would be contingent upon various border-security upgrades.

Some immigrants would have to wait as long as 10 years with this “provisional” status before being eligible for a green card. In the meantime, they would be able to work legally in the U.S. and to travel abroad.

That is what matters most in Tonatico, a town of 7,500 that celebrates a “Day of the Absent Migrant” during the annual fiesta that begins in late January. This hilly, long-struggling patch of Mexico has been sending migrants north since the 1940s, when many people here took part in the bracero program launched to help make up for U.S. wartime labor shortages.

When the second great wave of immigration began, in the 1980s, the undocumented were often able to return home without much trouble. They would drive across the border for birthdays, or Mexican Independence Day, or the Tonatico fiesta, then head back to their jobs in the U.S.

Crossing without papers was always a tricky proposition, but it became increasingly difficult after the Sept. 11, 2001, terrorist attacks, when Washington clamped down on the border. More recently, Mexican organized crime groups have targeted northern-bound migrants for extortion, robbery and kidnapping.

Some of Tonatico’s immigrants still come home to visit, but these days it’s only the ones authorized to live in the U.S. Their big trucks, with U.S. license plates, are a common sight on the major holidays.

On the recent Saturday, a white SUV with California plates was parked in front of Tonatico’s graceful, whitewashed church. The car’s owner never appeared, but the evidence of a growing biculturalism, fueled by years of cross-border exchange, was everywhere.

Aviles, the deported photographer, was hanging out in front of the church with the latest camera gear; he said proudly, and in nearly flawless English, that he had learned to use the Internet to shop for cheap electronics when he was in the States.

A few blocks away, Santos Colin Vazquez, 40, was relaxing with his wife and children in the four-bedroom luxury home he built with the money he made while working without a green card, between 1995 and 2004, in a factory in Waukegan, Ill.

Colin came home to Tonatico of his own volition, he said, “because the famous amnesty” — promised in previous failed congressional reform efforts — “never arrived.”

He was asked about the new bill’s chances of passage. “What I hope is yes,” he said. “What I think is no.”

Juan Romero Mendoza, 25, from the neighboring state of Michoacan, said he had worked without a green card as a house framer in Atlanta. Then the real estate market crashed and the work dried up. He returned to Mexico in 2007.

Romero, who was selling homemade furniture on the sidewalk across from the town market, said he was most intrigued by the Senate bill’s proposal to expand temporary guest-worker programs. He said he would love an easy way to make American money, but not have to commit to a full-time life in the U.S.

“The only reason most of us go up there is for un dinerito,” he said — a little money.

In the afternoon, Luis Sotelo, a Tonatico artist and activist, offered a tour of the city’s residential streets, showing how money from newly returned migrants — and remittances from those living abroad — had changed the lifestyles of many families here. Old, tired adobe buildings stood next to buildings with new facades, new additions and fresh coats of paint.

“This one with pesos, this one with dolares,” he said, over and over, pointing from house to house. “The story of Tonatico is written in the houses.”

What was missing, in so many cases, were the very immigrants who had sent the dollars but could not return to see what their dollars had built.

“It’s like a cage,” Aviles said of the immigrants stuck in the U.S. “The gold cage, I call it.”

The Senate immigration bill has sparked what is likely to be a long, messy debate in Washington, with some Republican members of Congress favoring a piecemeal approach to reform. Amid all this, the “registered provisional immigrant” proposal is bound to be one of the most controversial elements: Conservatives have long decried such a move as granting an undeserved “amnesty” to people who cheated the system.

Infighting on Capitol Hill felt both impossibly distant and tragically close that Saturday afternoon on a dusty mountainside outside of Tonatico, in a community called Salinas.

There, by a rustic adobe farmhouse, dozens of friends and family had gathered for a birthday party. The host, Patricia Gutierrez, had spent 11 years without legal status in the United States. Later, she married a U.S. citizen and earned her residency status. Now the professional tax preparer flies back frequently from her home in Nashville, throwing parties for her family at the adobe house she bought for that one purpose.

Sotelo, still playing guide, introduced guest after guest who had a family member stuck in the States. Teacher Josefina Dominguez, 51, said that two of her brothers have legal U.S. resident status. But two of them don’t. They haven’t been home to Mexico in 18 years.

Facebook and other social networks help keep her family connected across the fortified border.

“But sometimes,” she said, “you need to be with your family physically.”

Times staff writer Brian Bennett in Washington contributed to this report.

Originally posted at www.latimes.com:

Originally posted at www.latimes.com:

MEXICO CITY — Responding to mounting concern about disorder in the Mexican state of Michoacan, officials announced Thursday that an army general would take over as its public security chief, overseeing both state and federal security forces.

The appointment of the general, Alberto Reyes Vaca, was announced by state officials but had been arranged in coordination with the federal government.

For President Enrique Peña Nieto’s administration, the move is part of a promised new focus on the southwestern state, long a hotbed of drug cartel violence. It has been the scene of massacres, paralyzing labor strikes and clashes between new citizen vigilante groups and local officials.

Reyes, a career army officer, is a native of Michoacan who has, among other things, served as commander of a special forces battalion. His predecessor, Leopoldo Hernandez, had held the job for two months.

Interior Minister Miguel Angel Osorio Chong said Wednesday in a preview of the appointment that the public security chief would have the power to control and coordinate state and federal police, as well as federal troops deployed in Michoacan.

“There will be no public security secretary in any part of the republic who will have as much power as he has,” Osorio Chong said in a radio interview.

Peña Nieto’s team has been trying to steer attention away from Mexican security issues while emphasizing the country’s economic potential. Although violence remains a serious concern in many states, Michoacan, along with neighboring Guerrero, has been generating headlines that are particularly difficult to ignore.

In swaths of both states, dozens of “self-defense” groups, usually made up of armed masked men, have emerged, purporting to protect their rural communities from the drug cartels. But recent experiences in the troubled municipality of Buenavista Tomatlan demonstrate how complicated, murky and dangerous the situation has become in parts of Michoacan.

A Buenavista Tomatlan vigilante group formed in February and soon after detained a local police chief and a number of officers, accusing them of criminal connections. The army, in turn, arrested 35 members of the vigilante group in March, alleging they were members of a drug cartel.

This month, a reporter for the newspaper Milenio traveled to La Ruana, a city of 10,000 in the municipality, and found food, gas and medicine shortages, boarded up shops and a population terrified by the presence of a cartel called the Knights Templar. Residents complained that the cartel had stifled commerce in an effort to control the area. A month earlier, in nearby Apatzingan, armed men killed 10 lime pickers. The residents said the government was doing little to help.

On Wednesday night, according to federal prosecutors, federal troops detained 12 members of a self-defense group near the city of Uruapan, confiscating a number semiautomatic rifles.

Some grocery suppliers, including the Bimbo bread company, have said there are regions where the cartels have made it impossible to deliver food. At the same time, angry education students protesting a recently approved federal education reform have reportedly been detaining police officers and stealing trucks and buses, using them to block roads.

The governor of Michoacan, Fausto Vallejo, is a member of Peña Nieto’s Institutional Revolutionary Party. He has been ill for a number of weeks, and the state is being run by an interim governor.

This week, senators of the opposition National Action Party, concerned about the chaos in the state, began working on a proposal that would allow the Senate to replace Vallejo with a provisional governor, who would then call a new election.

Sanchez is a news assistant in The Times’ Mexico City bureau.

Originally posted at www.latimes.com:

MEXICO CITY — He’s got to be wishing that his daughter had just ordered takeout and gone home.

The head of Mexico’s consumer protection agency, Humberto Benitez Treviño, was fired Wednesday by President Enrique Peña Nieto, nearly three weeks after Benitez’s daughter sparked a restaurant scandal that made her Internet infamous and sparked a national conversation about the petulance and lingering sense of entitlement of the Mexican ruling classes.

On April 26, Andrea Benitez Gonzalez tried to score a table at one of Mexico City’s hottest restaurants, Maximo Bistrot, during the Friday lunch rush, even though she didn’t have a reservation. When the staff refused to give her the table she wanted, she threatened to call her father and have the place shut down, according to reports.

Soon, inspectors from the agency, known by its Spanish acronym, Profeco, arrived and alleged that Maximo Bistrot had violated rules regarding reservation policies and the labeling of some of the mescal they served. The daughter, meanwhile, went on Twitter to complain about the lousy service.

But Twitter, in the main, turned against her. As the news broke, other online commenters dubbed her “Lady Profeco.” Benitez’s face was inserted into satirical cartoons that imagined her calling her father and demanding that he shut down humble taco stands and popsicle vendors. (link in Spanish)

Suddenly, it seemed, Mexican columnists and taxi drivers were discussing the entitlement culture of the Mexican rich and, in particular, the powerful elites connected to the Institutional Revolutionary Party, or PRI, to which Andrea Benitez’s father belongs.

In December, Peña Nieto became the first PRI candidate to be sworn in as president in 12 years. Critics have been concerned that the party, which ruled Mexico in a quasi-authoritarian style for most of the 20th century, aims to turn back the clock, in part by granting favors to a well-connected few.

That criticism appeared to be very much on the mind of Mexican Interior Minister Miguel Angel Osorio Chong on Wednesday when he announced the firing of Humberto Benitez at a news conference. Osorio Chong declared that the although the father “didn’t order or participate in” the incident, Peña Nieto was still letting him go because the case had “tarnished the image and prestige” of the agency.

“With this decision the president of the republic sends a clear message to all of the public servants of the republic … that we are obliged to act in an ethical manner and absolute professionalism,” Osorio Chong said.

Cecilia Sanchez of The Times Mexico City bureau contributed to this report.

One of the world’s most dangerous volcanoes is rumbling and spewing and generally in a foul mood. Officials in the state of Puebla have opened shelters for potential evacuations. The Onion-like satirical website eldeforma.com has introduced the idea of sacrificing one member of the Mexican congress every hour in an effort to calm Popo.

Photo: CENAPRED

The youth-fueled #YoSoy132 movement met Saturday night under Mexico City’s Estela de Luz to celebrate the one-year anniversary of the student standoff with then-candidate Enrique Peña Nieto that triggered a movement that some observers dubbed the “Mexican Spring.” The YoSoy movement put thousands of protesters in the streets after last summer’s elections, who argued that Peña Nieto’s Institutional Revolutionary Party had resorted to vote-buying and other dirty tricks to sway the election in their candidate’s favor.

The spontaneous emergence of a group of millenials clamoring for a more open society and a purer democracy resonated deeply in Mexico, where slain student protesters during protests in 1968 are considered martyrs and national heroes. At the same time, YoSoy’s media savvy, sense of humor and use of social media suggested that a fresh new political voice had arrived on the scene.

I spent some time with the YoSoy movement last summer, and wondered whether they would be able to sustain momentum. There were formal legal challenges to Peña Nieto’s election at the time, but they ended up going nowhere. And Mexican presidents serve six-year terms — a long time to keep a nascent citizen political movement going.

Last night, the crowd was much smaller than the summer gatherings, but it showed that the movement is not dead. It may only be in hibernation, capable of being awakened by a flurry of tweets.

(No matter what happens to YoSoy–and no matter what you think of their politics–they are, without question, responsible for one of the best Latin American protests songs in recent memory.)

Photo: YoSoy#132 members watch a greatest-hits video of what they’ve achieved, May 11. [RF]

Originally posted at www.latimes.com:

By Richard Fausset, Los Angeles Times

8:03 PM PDT, May 10, 2013

MEXICO CITY — Efrain Rios Montt, the former Guatemalan military dictator who ruled his country during one of the bloodiest phases of its civil war, was found guilty of genocide and crimes against humanity Friday for the systematic massacre of more than 1,700 Maya people. He was sentenced to 80 years in prison.

The landmark ruling by a panel of three Guatemalan judges came after a dramatic trial that featured testimony from dozens of ethnic Ixil Maya, who described atrocities committed by the army and security forces who sought to clean the countryside of Marxist guerrillas and their sympathizers during the 1982-83 period that Rios Montt, an army general and coup leader, served as the country’s de facto leader.

Human rights advocates for years had been hoping for such a ruling.

A report by the country’s truth and reconciliation commission listed widespread human rights abuses during the civil war, which lasted from 1961 to 1996 and claimed more than 200,000 lives. The commission found that 93% of the rights violations were committed by the government or its paramilitary allies. But few leaders from the time have been brought to justice.

On Friday evening, Reed Brody, a spokesman for Human Rights Watch, called the decision a “historic verdict in a country where the rich and powerful have always been above the law, and impunity for atrocities has been the norm.”

But the nation’s highest-profile criminal trial in recent history was also derided from the start by Guatemalan conservatives, many of whom consider Rios Montt a heroic bulwark against communism.

Ricardo Mendez Ruiz, a Guatemalan businessman, is among those who have accused Guatemala’s top prosecutor, Claudia Paz y Paz, of harboring sympathy for the guerrillas. In an interview Friday, Mendez portrayed the entire case as an act of left-wing vengeance.

“The communists tried to take executive power by violence and they failed,” said Mendez, whose father served as interior minister under Rios Montt. “They tried to take legislative power by the ballot box and they failed. But they did take judicial power.”

During the trial, which began March 19, Guatemalan prosecutors accused Rios Montt of responsibility for the massacre of more than 1,700 Ixil Maya, as well as systematic rapes, torture and the burning of villages.

Rios Montt and his attorneys had argued that as the country’s political leader he should not be held responsible for military matters that occurred in a rural province a few hours northwest of the capital.

“I never authorized, I never signed, I never proposed, I never ordered that a race, ethnicity or religion be attacked,” the 86-year-old Rios Montt said in a statement to the court Thursday.

But the judges found that responsibility eventually rested with the dictator.

“Rios Montt was aware of everything that was happening and did not stop it, despite having the power to stop it,” Judge Yassmin Barrios said in the packed Guatemala City courtroom, which on numerous occasions erupted in applause.

The trial could have ramifications for the current president, Otto Perez Molina, a former army officer who commanded troops in the Ixil area during Rios Montt’s rule. Last month, a witness named Hugo Ramiro Leonardo Reyes, a former soldier, told the court that Perez had ordered the burning of villages and the execution of fleeing residents.

Perez denies the accusations and says he has never met his accuser. He enjoys immunity from criminal prosecution for the duration of his presidential term, which ends in 2016.

Rios Montt’s intelligence chief, Jose Mauricio Rodriguez Sanchez, also faced charges of genocide and crimes against humanity, but the judges acquitted him Friday.

Rios Montt was ordered to be sent directly to prison. In the chaotic scene after the verdict was read, he told reporters: “Don’t worry. I’m going to prison. I’m sorry for my family, but I’m not worried because I followed the law. Today there was a deficiency of justice.”

Cecilia Sanchez of The Times’ Mexico City bureau contributed to this report.

Copyright © 2013, Los Angeles Times

Above: A time-capsule news report from Guatemala’s darkest hours, 1982.

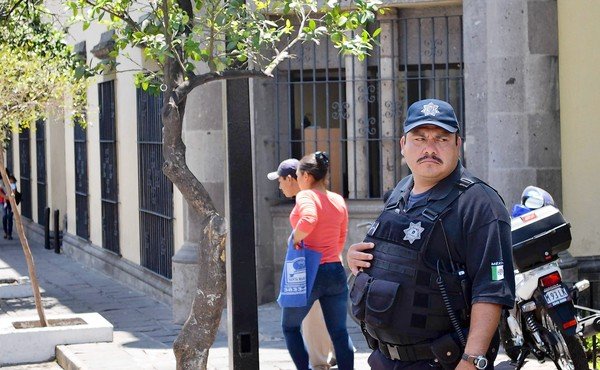

If Mexico is going to solve its crime problem, it needs clean police officers, from the bottom up. Under former president Felipe Calderon, Mexico initiated a plan to give every single officer in the country a “control de confianza,” or vetting test. A good idea on paper, perhaps, but its implementation has been a complicated mess. Among other things, there is a concern that cops who fail and are fired will be recruited by the drug cartels. (Of course some are working for them already). Read the story here.

Photo: A police officer patrols in downtown Zapopan, outside Guadalajara, Mexico. The mayor’s office there recently learned that of the roughly 1,600 police officers who had taken a trustworthiness test, 389 had failed. [RF]