A stall in the open-air market in Guatemala, just across the border from Talisman, Mexico. [RF]

This is the Mexican punk musician Juan Cirerol. He calls his songs “anarco-corridos,” and this one, “Eso Es Correcto Señor (Yo Vengo de Mexicali)” is a pure rush of adrenalin, stealing heavily from the first Bob Dylan record (the thieving Bob would surely approve), and borrowing a few bars of Jimmie Rodgers-style yodeling–but with a boozy, ragged sensibility that is pure norteño.

The lyrics are pretty straightforward: “That’s right, sir, I come from Mexicali,” he wails, which explains why he wears cowboy boots and denim, and why he drinks Tecate (the local brew). Life, he tells us, exists for us to enjoy it. So, slurp on that Tecate, and have “un toque push” while you’re at it (the slang is unknown to me, but I’m assuming that “push” isn’t Earl Grey).

Cirerol tells us he is a “Cachanilla,” which is the demonym for the people who live in Mexicali. It is a tip of the hat to the classic regional anthem “Puro Cachanilla” (which you can hear the great Vicente Fernandez do here), and part of a long tradition of geographic hyper-specificity in Mexican pop: Whether in name or in song, musicians here are inclined to tell you exactly where they’re from.

Cirerol’s new album is available for download in its entirety here.

This is a video I shot in an effort to capture the insanity of Mexico City traffic. The idea was to post the video alongside my article on the topic the other day. I had a feeling it was going to be difficult to capture just how wild and frightening it is to drive here: unless you are a witness to an accident, it’s really difficult to convey the madness with a video camera.

The piece turned out sort of tranquil and woozy–not matching the theme or tenor of the article, but perhaps interesting in its own way. We 86ed it as an official LA Times product. But here it is as samizdat–a snippet of a codeine dream of the Mexico City streets.

Originally posted at www.latimes.com:

MEXICO UNDER SIEGE

MEXICO CITY — Miguel Angel Mancera, the former top prosecutor in Mexico’s capital, rode his crime-fighting reputation to the mayor’s office, promising voters a superior level of safety as the cornerstone of a revitalized metropolis.

But six months into his term, Mancera, is fighting accusations that he has mishandled the highest-profile case of his mayoral career: the disappearances last month of 12 people from a bar in the heart of Mexico City.

The case remains unsolved, and the criticism of Mancera, a potential presidential candidate for the left-wing Democratic Revolution Party, or PRD, has been withering.

Mancera suffers from “political autism,” wrote a columnist on the website Sin Embargo. The mayor has not proved to be “a distinct or distinguished head of government,” declared a writer for Proceso newsmagazine.

Perhaps even worse for Mancera is that the disappearances, along with other recent acts of violence, have sparked a national debate about whether Mexico City is lapsing into a period of destabilizing drug-gang violence after several years as an oasis of calm compared with other Mexican cities.

Many think the answer is no. But then again, nobody knows for sure.

“I would like to believe, as an inhabitant of this city, that it is not, but I cannot rule it out,” said Juan Francisco Torres Landa, secretary of the civic group Mexico United Against Crime.

The capital’s reputation as a haven from cartel violence in recent years has made it a magnet for Mexicans whose cities have been beset by shootouts, beheadings and streets blockaded by burning cars. But horrors loom nearby, particularly in the neighboring states of Morelos, the province of the Beltran Leyva cartel, and Mexico, which is dominated by the cartel known as La Familia.

Mexico City is by no means perfect. The U.S. State Department says armed robberies, street crime and kidnappings are “daily concerns.” The 2011 homicide rate of 8.8 per 100,000 residents in the federal district, which encompasses the capital, was roughly one-tenth the rate for the northern state of Chihuahua.

Occasionally, there are outbursts of spectacular public violence of the kind considered a cartel-war hallmark. Last June, federal police said to be protecting a drug smuggling operation killed three fellow officers in the middle of the bustling Mexico City airport.

As a mayoral candidate, Mancera took some credit for the plummeting city crime rate during his time as top prosecutor, including a 12.5% reduction from 2010 to 2011, under the administration of Mayor Marcelo Ebrard. Mancera won the election handily and took office in December.

But even if Mancera can boast that he helped reduce the high levels of crime that once beset Mexico City, it would be difficult for him to ensure a safe environment if organized crime groups have in fact decided to launch a period of terror.

The mayor last week pressured his team to solve the case of the 12 disappearances, telling reporters that “no one is guaranteed a place in my government if they don’t get results.” On Tuesday, the city prosecutor’s office announced that the head of the missing persons bureau, Francisco Carlos Trujillo Fuentes, had stepped down and was being replaced.

Numerous theories exist as to why safety improved in this city of 20 million people during Ebrard’s tenure.

Supporters say the Ebrard team was wise to install thousands of video cameras, hire sharp, innovative police leaders and develop social programs to give kids alternatives to crime. Others suspect that the drug cartel bosses have designated Mexico City as a “safe zone” for their families, which has prevented it from becoming an urban battleground the way cities such as Ciudad Juarez, Monterrey and Guadalajara have in recent years.

Jorge Chabat, a professor at the city’s Center for Economic Research and Teaching, said cartel bosses may have been operating under the assumption that major crimes would generate much more attention in the media-saturated capital than elsewhere and result in more heat from authorities.

A report from the Mexico City Citizen Council shows some homicide and gun-related statistics up slightly in the first five months of this year compared with the same period last year. But auto thefts and home-invasion robberies have declined.

Torres said the May 26 disappearances of the 12 young men and women, whose ages ranged from 16 to 34, garnered more media attention than other similar crimes because they occurred in the Zona Rosa, or Pink Zone — a centrally located, formerly trendy neighborhood that has fallen on hard times but is nonetheless well known to the Mexican elite.

In tougher, working-class neighborhoods, Torres said, “they’d probably say, ‘Why are you guys so concerned about this? This is what happens every day in this city.'”

The details of the disappearances are murky. Family members said the bar patrons had been stuffed into SUVs by armed, masked men, a hallmark of mass kidnappings in other Mexican cities. But city prosecutor Rodolfo Rios has shared surveillance tapes that show the bar patrons being loaded into a number of compact cars by men who do not appear armed or masked. Rios said authorities could place only eight of the 12 missing people at the bar.

Rios said the disappearances may have involved a rivalry between local drug gangs. The missing all hail from Tepito, a neighborhood notorious for counterfeiting and other criminal operations.

Prosecutors have acknowledged that one of the missing, 16-year-old Jerzy Ortiz Ponce, is the son of Jorge “The Tank” Ortiz Reyes, the incarcerated leader of a Tepito neighborhood drug gang. Another of the missing, Said Sanchez, is the son of Alejandro “El Papis” Sanchez, who is serving time for homicide, robbery and extortion, according to local news reports.

On June 6, two masked gunmen entered a gym in Tepito and killed four men. Authorities do not believe the attack is related to the disappearances. More recently, a Mexican journalist revealed that five other missing people were last seen at another bar in a different part of town.

In a separate incident in early May, the grandson of the late Malcolm X, Malcolm Shabazz, was killed in a fight at another Mexico City bar and two suspects were arrested.

Mancera’s government, which has sent hundreds of additional police officers to Tepito and the Zona Rosa, has vowed to watch over nightclubs to prevent further disappearances.

The mayor has denied that the Zona Rosa disappearances had anything to do with the drug cartels and that cartels are operating in the capital.

Torres and others think that Mexico’s big, infamous, multinational criminal organizations are certainly hanging around the megacity, even if they have been keeping a low profile.

Chabat said that Mexico City is home to criminal groups of all sizes. Some of the smaller ones, he said, though not technically cartels, probably have close links to the larger groups.

Ultimately, if Mancera wants to stay alive politically, he will almost certainly be expected to keep all of them, big and small, in check.

Cecilia Sanchez of The Times’ Mexico City bureau contributed to this report.

This row of pickup truck pieces, lined up in a Guatemalan salvage yard just across from Talisman, Chiapas, Mexico, reminded me of the abstract sculptures of the late John Chamberlain.

Photo: [RF]

“It’s the mouth of a volcano. Yes, mouth; and lava tongue. A body, a monstrous living body, both male and female. It emits, ejects. It is also an interior, an abyss.” — Susan Sontag.

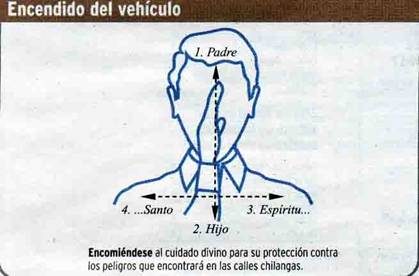

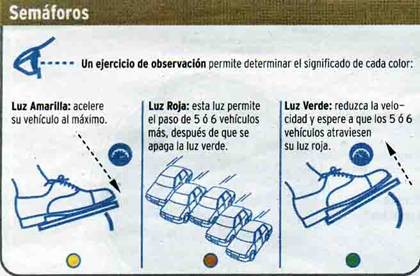

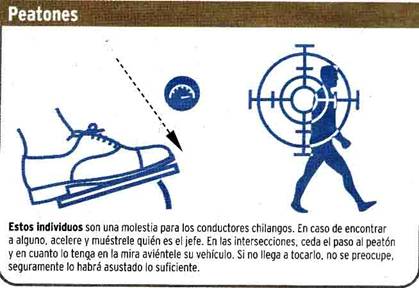

A friend sent this “Mexico City Driving Manual” after reading my piece on the subject earlier this week. If you don’t read Spanish, you should still get an idea of the tenor of this tongue-in-cheek guide from the illustration in the first panel, which suggests making the sign of the cross before cranking the ignition. The instructions become increasingly less holy from there.

Originally posted at www.latimes.com:

MEXICO CITY — Powerful Mexican drug boss Rafael Caro Quintero was off the streets in 1985, arrested in Costa Rica on suspicion of ordering a hit on a U.S. drug agent. His fate appeared to be sealed in 1989, when a Mexican judge convicted him and sentenced him to 40 years in prison.

It has been a long time since Caro’s halcyon days when, according to a Times article in 1992, he was the guest of honor at lavish parties, including one where he flamboyantly smoked cocaine while on the back of a dancing horse.

And apparently Caro’s influence lives on, according to the U.S. Treasury Department, particularly in the city of Guadalajara, Mexico’s second-largest metropolis. His dirty money is allegedly bankrolling construction and real estate projects, a luxury spa, restaurants, a shoe store, gas stations and a swimming pool company.

On Wednesday, the Treasury Department announced that 18 people — including Caro’s four children, wife and daughter-in-law — as well as 15 businesses linked to him had been “designated” under the Foreign Narcotics Kingpin Designation Act. The designation prohibits Americans from doing business with them and freezes any assets they may have in banks under U.S. jurisdiction.

It far from clear what kind of effect the designation will have: In 2011, The Times found that a number of Mexican businesses blacklisted by the U.S. remained in business.

But the alleged extent of Caro’s continuing influence offers a look at the way laundered narco fortunes — even those earned by kingpins locked away long ago — continue to make powerful waves in Mexico, bankrolling some of the most mundane commercial ventures.

It also demonstrates that U.S. law enforcement officials have long memories, particularly when it comes to cases in which one their own was slain. In this case, Enrique “Kiki” Camarena, an undercover Drug Enforcement Administration agent, had been targeting Caro’s massive marijuana growing business. One operation resulted in the seizure of more than $50 million in marijuana. Camarena was eventually kidnapped, interrogated, tortured with burning cigarettes and killed.

The U.S. government launched a massive homicide investigation that resulted in a number of convictions of people involved in the plot, including the brother-in-law of former Mexican President Luis Echeverria. The story also generated hundreds of newspaper articles as various cases made their way through the Mexican and U.S. court systems.

Caro’s Guadalajara drug cartel, meanwhile, has long ceased to be the massive player it once was. But Gary Haff, the acting chief of the financial operations section for the DEA, made it clear in a statement Wednesday that his agency remembers.

“No amount of effort can clean [the drug dealers’] dirty money, paid for with their violence and by their victims, including DEA Special Agent Kiki Camarena,” he said. “DEA is committed to seeing that justice is done, and we will not rest until they and their global criminal networks have been put out of business, their assets have been seized, and their freedom has been taken from them.”

Guadalajara, capital of the southwestern state of Jalisco, has long been known as a city where narco bosses live, shop and send their children to school. The Treasury Department statement said the designated businesses included a bath- and beauty-products store called El Baño de Maria, a restaurant called Barbaresco and a resort spa called Hacienda Las Limas.

On the travel website Tripadvisor, reviewers generally enjoyed their stay at Hacienda Las Limas. Their apparent ignorance of the alleged “dirty money” behind the place may come to be viewed as one of the defining conditions of the current Mexican era, a time when the stain of drug profits is difficult to detect and, at this point, probably impossible to erase:

“the service is beyond excellent. white terry cloth robes, huge beds, good sauna, hot tubs, small pool,” wrote a capitalization-averse guest named jeff p from Park City, Utah. “and unlike most spas you can have alcoholic drinks or smoke a cigar, or request a steak for dinner if you like.”

Originally published at www.latimes.com:

MEXICO CITY — It was the kind of big-man boast that would have made Jay-Z or Bo Diddley proud: He owned 300 suits, he said. Four hundred pairs of pants, 1,000 shirts and 400 pairs of shoes. He shopped Beverly Hills, Rodeo Drive, “the best of Los Angeles.”

Unfortunately for Andres Granier, the ex-governor of the state of Tabasco, his fellow Mexicans are in no mood to hear such stuff from the political class.

Granier’s comments were surreptitiously recorded in October at a Mexico City party, and they have not helped his current predicament: State and federal prosecutors are pursuing criminal investigations of whether Granier and his team mishandled millions of dollars in state funds before leaving office in December.

The probes appear to be heating up. On Saturday, federal officials arrested Granier’s former state treasurer, Jose Saiz, at the U.S. border on suspicion of embezzlement. Earlier this month, a photo of Saiz with a red Ferrari surfaced. His attorney said Saiz bought the car with money he earned in the private sector.

On Wednesday, Granier — who has said his recorded boasts were untrue and made while drunk — was in Mexico City, where he planned to give a declaration to federal prosecutors behind closed doors. He asserted his innocence shortly after flying in from his home in Miami.

“I come to clear my name,” he told reporters at the airport. “I have no reason to run.”

Mexicans are watching the investigations of the former governor and his aides closely. Granier, 65, is a member of the Institutional Revolutionary Party, or PRI, which returned to the presidency in December after a 12-year hiatus, promising it would not indulge in the kind of old-school trickery and self-enrichment that marked its seven decades of quasi-authoritarian national rule.

After the government arrested flamboyant union boss Elba Esther Gordillo on corruption charges in February, President Enrique Peña Nieto went on national television and declared that in Mexico “no one is above the law.” Mexicans are waiting to see whether the government will follow through.

If, as many suspect, there are entrenched forces within the PRI who would rather hide the party’s sins, their task is complicated by media that, in the Mexican capital at least, are more feisty than in the old days. Social media users also keep the heat on, particularly through Twitter, where they have unleashed excoriating satire directed at those who appear to be indulging in the old soberbia, or arrogance.

The Peña Nieto government appeared to get the message last month when it fired the head of the federal consumer protection agency, Humberto Benitez Treviño. Benitez had been in the hot seat after his daughter apparently called out inspectors to close down a restaurant where she had been denied a good table. The episode had turned her into a kind of Public Enemy No. 1 on Twitter.

Federal prosecutors also launched an investigation, since turned over to state authorities, of a loan scandal that left the Coahuila state government with a $3-billion debt after the term of Gov. Humberto Moreira ended in 2011. He later served as national chairman of the PRI.

In April, the Mexico City newspaper Reforma reported that Moreira was living outside Barcelona, Spain, in a luxury home with a $4,500 monthly rent. Moreira said he was living off personal savings and a pension he earned as a teacher.

Granier’s Tabasco state is one of the nation’s poorest; according to federal figures, 57% of Tabascans were living in poverty in 2010. At a news conference last month, Granier’s successor, Arturo Nuñez, who represents a coalition of leftist parties, said the financial administration of the state under Granier had been “a labyrinth of trickery, missing documentation and a debt of over 20 billion pesos” — about $1.5 billion.

Granier may find a way to prove that he broke no laws. But his assertion that his drunken boasts were untrue will probably continue to be a hard sell in a country with a popular saying that goes: Los niños y los borrachos siempre dicen la verdad. Children and drunks always tell the truth.

“Andres Granier is coming back to Mexico?” went one common joke on Twitter on Tuesday night. “How many shirts and shoes will he have in his suitcase?”

Sanchez is a news assistant in The Times’ Mexico City bureau.

Photo: Andres Granier, former governor of Mexico’s Tabasco state, arrives at the airport in Mexico City. He traveled from his home in Miami to meet with federal officials investigating the possible misuse of public funds during his term. (European Pressphoto Agency / June 13, 2013, via LA Times)