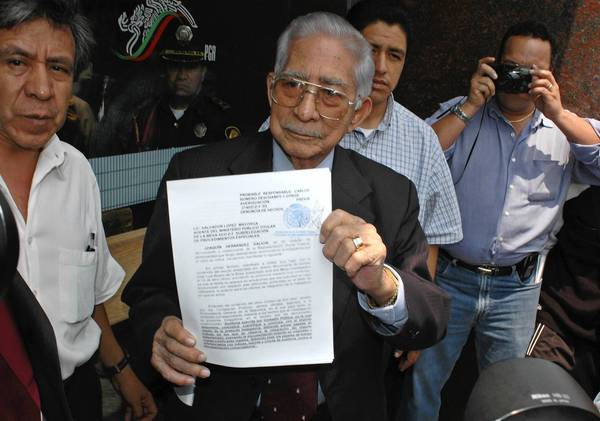

MEXICO CITY — To President Enrique Peña Nieto’s supporters, his first year in office has been a time of bold promises kept as he pursues an ambitious agenda of reforms designed, in the long term, to bring peace and economic growth to Mexico.

But in the short term, by many measures, his country remains a mess.

Though he promised to focus on Mexico’s economic potential, Peña Nieto has presided over an economy that has hardly grown at all. Though he vowed to reduce the kind of violence that affects innocent citizens, his record has been mixed, with kidnappings and extortion rising nationwide even as the number of homicides drops.

And the drug war rages on. In recent months, the key agricultural state of Michoacan has devolved into something close to a failed state, as armed peasants have formed ad hoc militias to protect themselves from the surging cartel menace. On Wednesday, the president’s finance minister, Luis Videgaray, declared that the ongoing chaos there was a threat to Mexico.

As Peña Nieto marks his first year in office, he has successfully pushed major banking, education, tax and telecommunication reform bills through Congress, and is pursuing changes in the crucial oil industry. Yet the young, confident and telegenic president, who as a candidate promised a “government that delivers,” is facing doubts about his ability to do just that.

A poll from El Universal newspaper last month put Peña Nieto’s approval at 50% and his disapproval at 37% — his worst numbers so far as president. In the newspaper Excelsior, columnist Leo Zuckermann last week noted that the president had failed to transform the positive story he tells about Mexico into actual good news.

“It was one thing to ‘sell’ great expectations, which the Peña government did very well,” Zuckermann wrote, “and another very different thing to deliver good results.”

On Sunday, thousands of the president’s critics marched in the historic center of Mexico City to protest his first year in office, and the idea of opening the state oil monopoly to foreign investment.

Some protesters threw rocks at a storefront and at the headquarters of Televisa, the giant TV network that many consider to be biased in Peña Nieto’s favor. Seven protesters were reportedly arrested.

The government expects the Mexican economy to grow by an anemic 1.3% this year, which many analysts blame largely on a troubled world economy.

The president, meanwhile, is asking his fellow Mexicans to give his big-picture agenda time to generate results.

“I am sure that the foundations that we are achieving will be very firm and solid, and will allow Mexico to have more economic growth and more social development,” Peña Nieto said at an October business summit in Guadalajara. “I’m convinced of it.”

While the president’s initiatives have included some ideas that could be considered liberal, including tax hikes and an anti-hunger program, others have sought to address the market distortions that linger from the last century, when his Institutional Revolutionary Party, or PRI, ruled Mexico with a dollop of socialism and a heap of corruption.

It may be a challenge, however, to convince Mexicans that a radical transformation is truly underway. This is a country with a history of passing beautifully constructed laws that often end up doing little to change the real-life status quo. Some critics argue that Peña Nieto and his allies have allowed key elements of their reform package to be watered down and made less effective as they compromised, trying to mollify often raucous special interest groups and opposition political parties who had agreed to a general reform framework in a so-called Pact for Mexico, signed just after Peña Nieto’s inauguration.

The education law, for example, has been criticized for not being tough enough on chronically underperforming educators: Teachers can be reassigned, but not fired, for repeatedly failing new evaluation tests. The law was passed over the fierce objections of a radical union whose protests choked Mexico City for weeks.

The tax proposal, meanwhile, sought to boost revenue in a country that has the lowest tax collection rates in the developed world. Though the law that eventually passed included some tax increases, a proposed sales tax on food and medicine was left out in an effort to placate the left.

Peña Nieto has yet to push through the most controversial change of all: a plan to open the bloated and inefficient state oil monopoly, Pemex, to foreign investment. The company supplies a third of the federal government’s income, but production is dwindling precipitously, and analysts say Pemex requires injections of foreign expertise and technology to turn itself around. But the constitution mandates that oil is the property of the Mexican people, and the issue touches deep chords of national pride.

Peña Nieto’s team has backed a proposal to share profits with foreign oil concerns, but not the cut of the petroleum itself that those companies would prefer.

The legislature could vote on the proposal by year’s end. Jorge Castañeda, a well-known intellectual, is among those who believe that the president and his team should get behind a production-sharing plan, or something like it, in hopes of delivering Mexico a dramatic economic boost.

“They know they have to do something more, that just profit-sharing is not going to do the job,” Castañeda said. “But they may or may not have the political capital left at this stage to do more. If they had done energy reform at the beginning, maybe it would have been easier.”

Meanwhile the left-wing Democratic Revolution Party, which opposes such measures, pulled out of the much-ballyhooed Pact for Mexico in protest.

On the crime front, federal figures show that homicides for the first 10 months of 2013 were down 16% compared with the same period in 2012, but extortion was up 10% and kidnappings up 33%. Such numbers come with multiple caveats: Prominent critics have charged that the government is manipulating the homicide statistics, while the extortion and kidnapping figures could reflect an increase in the reporting of crimes to authorities.

Peña Nieto has struggled in his efforts to resolve the conflict with the drug cartels that has left thousands of people dead and come to define the country in the eyes of the world. The president had hoped to lower his reliance on the military, which was sent into the streets by his predecessor to push back against the cartels. Yet when trouble escalated in Michoacan, Peña Nieto appeared to have little choice but to send in the troops.

As a candidate, Peña Nieto promised to create a paramilitary police force known as the “gendarmerie” to do some of the work the military is doing now. But its rollout has been delayed, and officials have changed their statements about its mission and makeup. “The gendarmerie,” says Mexican security expert Alejandro Hope, “is a joke.”

Last week, the international group Human Rights Watch sent an open letter to Peña Nieto accusing him of having a human rights strategy that was “largely confined to rhetoric” while lacking “a concrete plan” for combating violence.

In an interview, Sen. Ana Lilia Herrera of the PRI repeated the administration’s contention that there had been a fundamental change in security strategy, one that stressed better “coordination” among government officials.

Such is the rhetoric. Mexicans are waiting to see if it produces results.

richard.fausset@latimes.com